Celebrating Clay County History: The 14th Colony

As the 14th colony, Florida’s place in the Revolutionary War is often forgotten. When thinking about the American Revolution, folks think about the thirteen colonies north of Florida. Looking at …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Celebrating Clay County History: The 14th Colony

As the 14th colony, Florida’s place in the Revolutionary War is often forgotten. When thinking about the American Revolution, folks think about the thirteen colonies north of Florida. Looking at the big picture, the British colonies began with the British West Indies, ran through Florida and the thirteen other colonies, and then continued into the British Canadian colonies of Quebec, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and New Brunswick. St. Augustine and Florida in general were in the middle of the British Empire in the Western Hemisphere.

Then there was the attitude of British Floridians, who were happy with the status quo. While the upper thirteen had a beef with the British crown, East Floridians did not. Local plantations, especially those in Clay County, were thriving. East Floridians saw the Continental Congress as rabble-rousers who posed a great threat to an economy that was working in their favor. East Florida could feed itself, defend itself, and produce profits. Because of this success, Florida became a refuge for Loyalists fleeing the upper thirteen colonies.

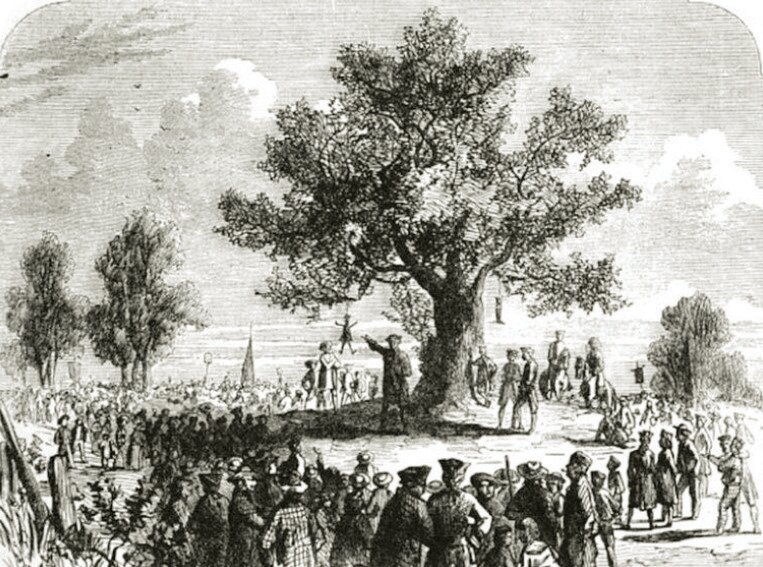

When news of the signing of the Declaration of Independence reached St. Augustine on August 11, 1776, a large mob of Loyalists burned the effigies of John Hancock and Samuel Adams in the town square. British East Florida, of course, sent no representatives to the Continental Congress. St. Augustine soon became a base of operations from which the British dealt with the southern colonies. Troops and munitions were amassed there, and refugees from the other thirteen colonies flooded the streets.

None of this went unnoticed by the rebel colonists. The Continental Army launched three attempts to conquer East Florida in 1776, 1777, and 1778. The first attempt was ordered by General George Washington himself. These ultimately failed, as it seems that the true grit needed to invade just wasn’t there. Lack of manpower, poor leadership, and logistical errors all led to these failures.

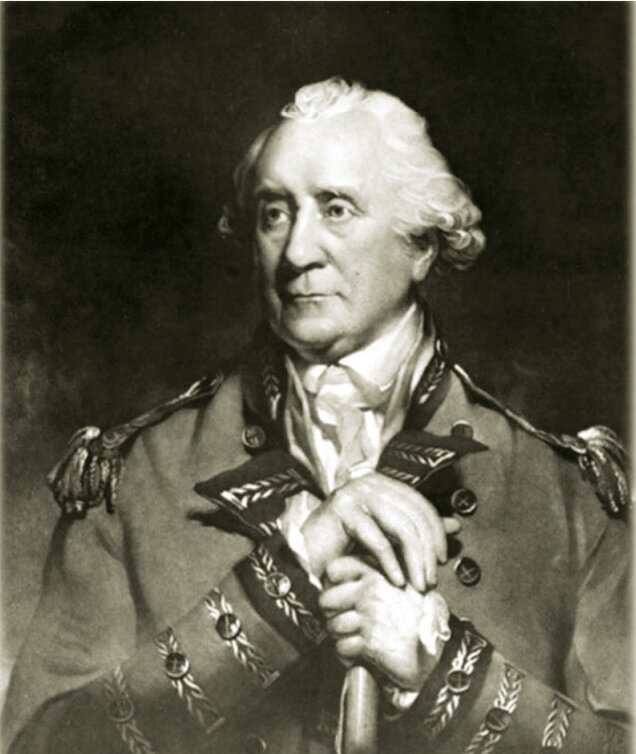

Sneaky raids by low-level rebels were one way that the Revolution affected East Florida. As a result, Governor Patrick Tonyn had to send several of his workers and slaves to St. Augustine to build public defenses. In order to keep property, houses, and other such assets out of the rebel’s hands, General Augustine Prevost decided to burn all “houses and manufactured timber” along the west and north of the St. Johns River and around Doctor’s Lake. Tonyn diligently carried out the order. He wrote that his orders were "fully executed”, and his own 20,000-acre plantation on Black Creek was totally destroyed. He lost two plantation homes, sixteen slave cabins, two barns, four sets of indigo vats, and 3,000 cypress planks.

The American Revolution brought raids and extensive damage to British East Florida. The ungrateful rebels saw Florida as a great resource for slaves, timber, cattle, cotton, and whatever else they could lay their hands on. Not all these raiders were whom we think of today as our Revolutionary War heroes; some were sometimes just small bands of raiders and bandits.

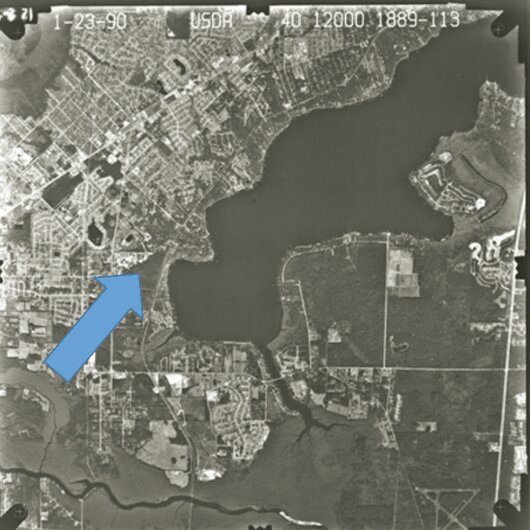

Over at Doctor’s Lake, Spring Garden and Tobacco Bluff were British indigo plantations. They were located on the western side of Doctor’s Lake and were the property of John Davis. When John Bartram, the Crown’s botanist, visited the area, he stayed with Davis. Spring Garden was 400 acres and Tobacco Bluff was 600 acres. Between 1774 and 1776, the sales of indigo exports from Spring Garden and Tobacco Bluff in London totaled £556 sterling. The land was considered excellent for timber and naval stores, and the set value of the property was £2844, including slaves. Indigo, tobacco, citrus, sugar cane, and Sea Island cotton were common crops.

On July 1, 1776, armed rebels from Georgia surrounded the slaves at Tobacco Bluff while they were at work in the fields. Twenty-seven men and women were abducted and marched to Georgia. The cattle, horses, hogs, indigo and provisions fields, a framed and weather-boarded barn, a log dwelling house, a mill house, slave dwellings, indigo vats, and poultry houses were destroyed or stolen.

The plundering of slaves in East Florida by American rebels was rampant. On July 1, 1776, Governor Tonyn reported that the theft of slaves was an obvious goal of the rebels as “they took upwards of thirty (slaves) and a family” from the first two plantations they reached. Tonyn was talking about Spring Garden and Tobacco Bluff. Plundered slaves were also used to carry other items taken from plantations, such as furniture, household goods, food stores, and farm equipment.

Tonyn dealt with the “unnatural colonists who are ungrateful to British designs,” as he called the rebels and Continental soldiers. He sent out his local militia, like Thomas Brown and Brown’s Rangers, after them. Many were arrested and brought back to the Castillo, where some were treated as prisoners of war and others like common criminals.

In 1779, Spain took advantage of Britain's total distraction with the Revolution. By 1781, Britain had lost West Florida to Spain. On September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution. Under a separate treaty, England ceded Florida back to Spanish control in exchange for the Bahamas, ending British Florida. The war, having drained Britain's coffers, resulted in Britain being forced to recognize American independence. After losing control of the majority of its colonies, Britain had little interest in keeping Florida.

No one was angrier about the abandonment then Governor Tonyn. Patrick Tonyn, who was so loyal to the Crown felt deeply betrayed. All his efforts to keep the colony safe and ensure its economic success were tossed aside. The “Great Evacuation”, as it was called, did not go well. Stretching the new Spanish governor’s patience, the British managed to turn an evacuation into an almost three-year ordeal. Then, Parliament, like a dog with a bone, demanded that he explain his management of the “Long Evacuation.” There were no parades welcoming back Governor Tonyn. Instead, he faced years of red tape and paperwork.

The Floridian colonists were not happy.