What if Spain Never Conquered La Florida?

CLAY COUNTY – It’s a farfetched and illogical situation to imagine, but “what if” Spain never conquered La Florida? What would Clay County look like today? We know, of course, that manifest …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

What if Spain Never Conquered La Florida?

CLAY COUNTY – It’s a farfetched and illogical situation to imagine, but “what if” Spain never conquered La Florida? What would Clay County look like today? We know, of course, that manifest destiny probably would have caused Florida to become an American territory regardless, but just for fun, let’s explore this question.

If not for Spain’s actions, Florida could have become a French colony. Floridians might now be speaking French if not for Pedro Menendez de Aviles’ 1565 attack on the fledgling French Huguenots’ colony at Fort Caroline. Aviles’ successful extermination of the French colonists became the first domino to fall in the long line of dominoes that led to Clay County’s existence.

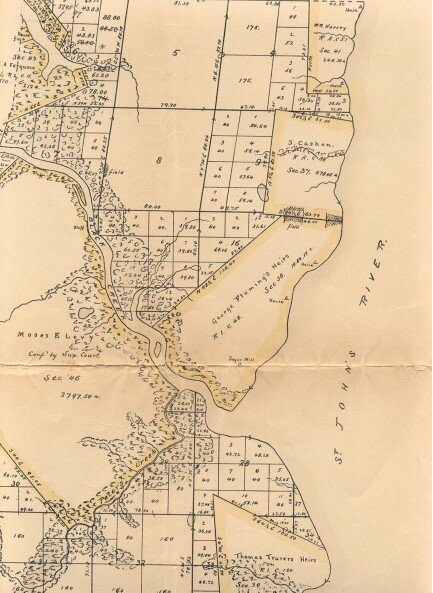

What if Spain hadn’t spread Catholicism across Florida? The first Spanish period (1565 to 1763) led to the creation of Fort San Francisco de Pupo in what is now Clay County. In 1675, Pupo was initially a ferry crossing, and it was the sister fort of Fort Picolata, which was directly across the St. Johns River on the east bank. Picolata protected the Mission San Diego de Salamototo. The Spanish friars traveled from St. Augustine to Picolata, then crossed the river to land on the Clay side. That was the Spanish mission trail’s starting point west across Florida.

The mission trail resulted from the efforts to Christianize the Native Americans that began shortly after Pedro Menendez’s victory over the French. Spanish colonists needed to build profitable Catholic settlements, and Spain also wanted to spread Catholicism amongst the native peoples. Since the local Timucua were semi-nomadic, missionaries needed to gather them into permanent settlements. This endeavor began the mission system and the subsequent Camino Real (King’s Road). This road later became known as the Bellamy Road (first federal highway in Florida), and it cut southwest across Clay County from land now known as the Bayard Conservation area to Melrose. Some parts of Bellamy Road are still used to this day. Without the Catholic goal, none of these things would have happened.

The British colonies north of Florida were not on good terms with the Spanish, as both sides regularly raided each other’s territory. When James Moore, the English governor of colonial Carolina, carried out attacks in 1704 and 1706, he succeeded in wiping out most Spanish missions in Florida. This loss caused the Spanish to build more forts and attack the British. Many believe this is when Fort San Francisco de Pupo was first built.

What if, in 1737, the Spanish Royal Engineer Arredondo had not taken notice of these two small forts? He found them falling and crumbling, and he recommended an immediate rebuilding and reinforcement due to the constant threat of British attacks. In 1740, with the beginning of the War of Jenkins Ear, General Oglethorpe, the British general from the colony of Georgia (of which he was a founder), chose this as an opportunity to invade St. Augustine. The Royal Engineer had great foresight.

General Oglethorpe began with raids on Pupo and Picolata. He landed his troops in a classic pincher movement, trapping Fort Pupo inhabitants between the river and his troops. Fort Pupo’s recent refortifications made it challenging to take the fort. The day-long artillery barrage that ensued gave the Spanish enough forewarning to prepare St. Augustine and successfully thwart the British invaders. If Oglethorpe’s invasion had been successful, the British could have acquired its 14th colony 23 years earlier than it did.

In 1818, George J. F. Clarke received a Spanish land grant, which included the fort. Later known as Bayard, it was part of Clarke’s 16,000-acre grant, which his heirs later sold. Sheriff John P. Hall eventually owned part of the property, creating the Bayard Conservation Area. Today, the fort site is on private property. What if, oh so many years ago, Hall had not vowed to preserve the site? Clay County citizens would have lost the opportunity to enjoy the land.

The British Period (1763-1783) happened because of the Seven Years’ War. Spain lost Cuba and the Philippines to Britain, then gave up Florida to get these valuable colonies back. The Treaty of Paris, signed on Feb. 10, 1763, relinquished ownership of Florida to the British.

Meanwhile, in what was to become Clay County, massive British indigo plantations were spreading along the shores of Doctors Lake and Black Creek. What if a colonist named A. E. Ferguson had not applied for a British land grant? Thankfully, he did. Otherwise, we might not have Whitey’s Fish Camp or the underwater archeological treasure called The Maple Leaf. Ferguson called his land grant Harmony Hall.

In later years, during the Civil War, the Harmony Hall lands were owned by Sheriff Joshua D. O’Hern. From there, he launched a successful sabotage campaign by mining the St. Johns River and sinking four Union ships. One was the troop transport, The Maple Leaf. In the 1990s, the wreck was excavated, which led to the most significant number of Civil War artifacts found in one place. Artifacts from the ship are at the Mandarin Museum in Jacksonville, and a smaller collection is in the Clay County Courthouse lobby in Green Cove Springs. Today, Whitey’s sits on the former plantation’s land and offers a great atmosphere, food and music. Also, a road in Doctors Inlet is named Harmony Hall.

The Second Spanish Period (1786 to 1821) brought a wave of settlers to Clay County, with Zephaniah Kingsley and George Fleming most notably among them. Without the Spanish, we would not have Fleming Island.

In 1812, the Patriots Rebellion, led by insurgents hostile to the Spanish crown, caused Ana Kingsley to burn down her and Zephaniah’s Laurel Grove Plantation. She did it to deny the rebels shelter and supplies. What if the rebels had succeeded in overthrowing Spain? We wouldn’t have Orange Park or Kingsley Avenue.

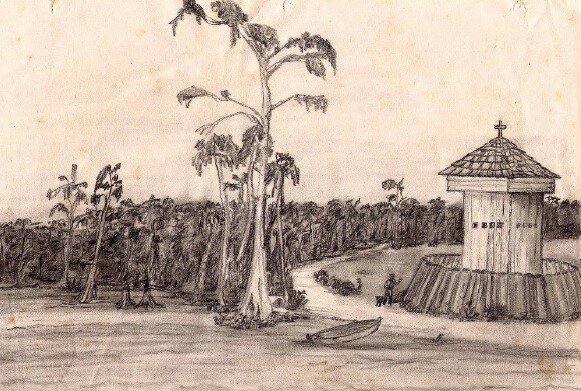

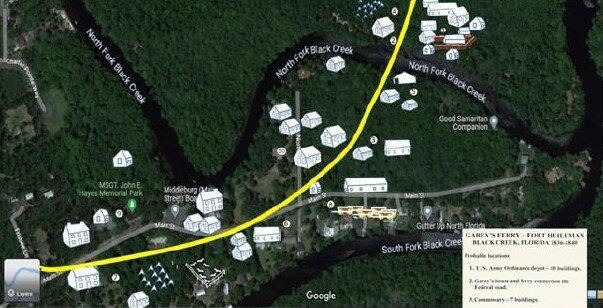

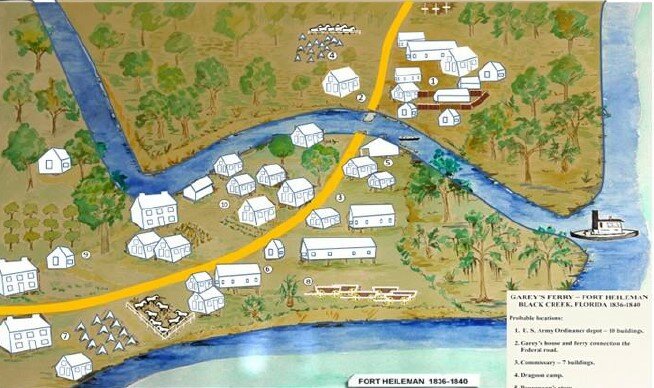

Fast forward to 1821. Spain was strong-armed into turning over La Florida to the United States. What if that never happened? We would not have Fort Heileman, Whitesville, or Middleburg later. The entire Black Creek District would not have existed; ultimately, we would not have Clay County.

There are so many other historical subjects from Clay County history that one can play this “what if” game. Residents and visitors are invited to the Clay County Archives to learn more from our staff and review original archival records and photographs. The Clerk’s Archives Center is open from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. most weekdays.

They encourage Clay Today readers to visit clayclerk.com (click on the Historical Archives button) to learn more, or call Archives at (904) 371-0027 to arrange your visit.