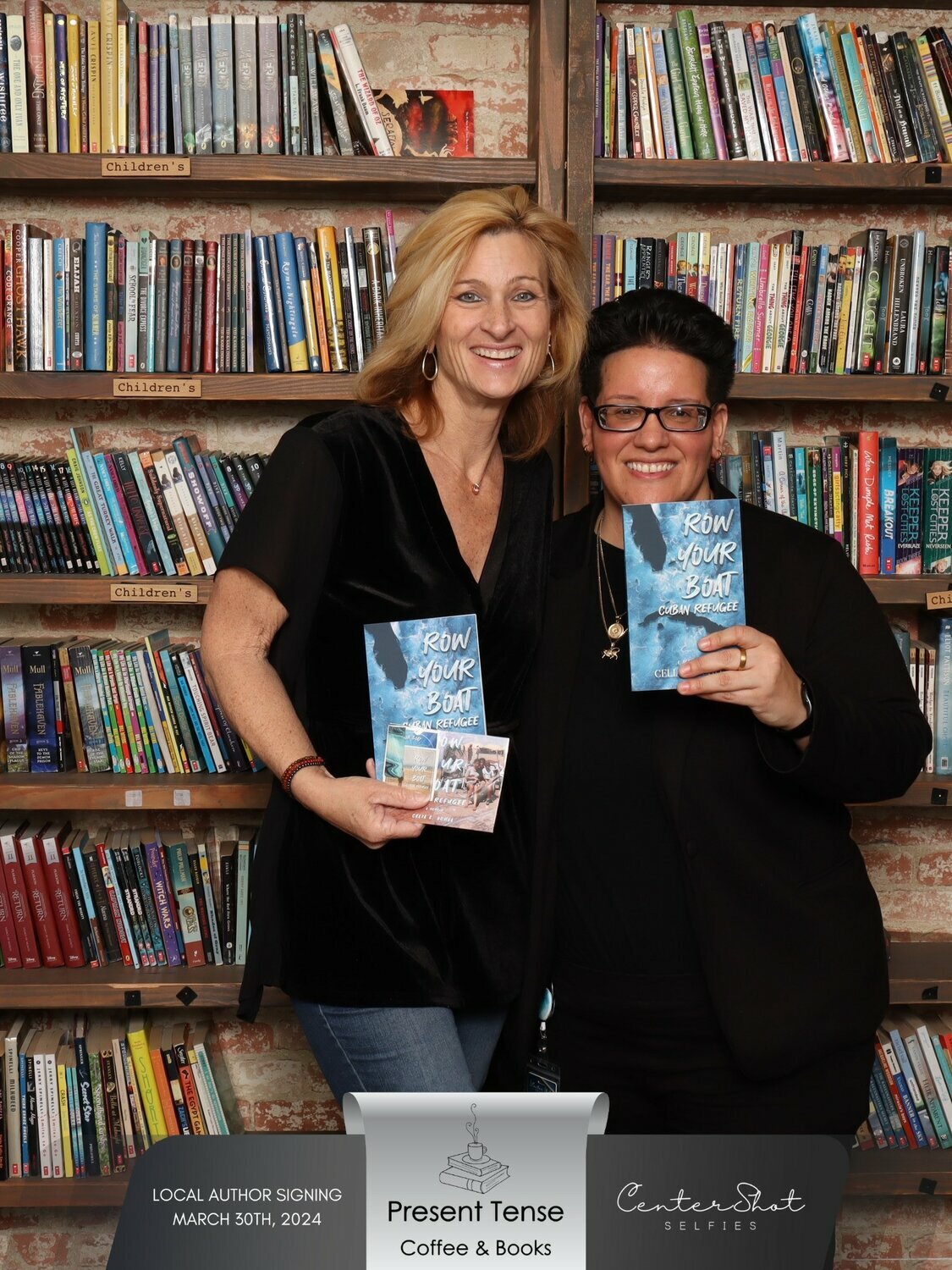

Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy petty officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

Impromptu meeting stirs memories, creates questions about their time together

jack@claytodayonline.com

With it being nearly 30 years ago, Celia E. Ochoa can’t say if Tanya Lea dropped a scoop of rice for them. Or a scoop of beans. Or handed her and her family MREs (meals ready to eat). Tanya …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy petty officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

Impromptu meeting stirs memories, creates questions about their time together

With it being nearly 30 years ago, Celia E. Ochoa can’t say if Tanya Lea dropped a scoop of rice for them. Or a scoop of beans. Or handed her and her family MREs (meals ready to eat).

Tanya can’t say for certain after reading the memoir and viewing each image.

But considering the odds it took to bring the women to the base in the first place, Celia thinks it was not unlikely they would have crossed paths. Her family moved around the base, and it’s not like they had other food options.

Celia currently lives in Middleburg with her wife. They have four children: two boys and two girls. Together, they own Center Shot Selfies, LLC, a photo booth rental company. The small business is an active Clay County Chamber of Commerce member.

Celia wrote her memoir hoping that someone – a guard, a refugee, a friend and anyone else she met along her way – would reach out from that time in her life.

By that metric, the memoir was a success just one year after its publication.

Tanya currently lives in Jacksonville and co-owns Consciously Aware Coaching and Consulting. Tanya made it her life mission to educate and understand the depth of human emotion and behavior, having struggled with her own for years. She is passionate about helping people see the “light at the end of the tunnel” and turn their tragedy and trauma into victory and triumph. She earned an M.A. in Mental Health Counseling, an MBA, and a Ph.D.

Tanya was the keynote speaker at Finally Friday, an event sponsored by the Clay Chamber, where she spoke about the assault and her struggle with mental health publicly for the first time.

Tanya met Celia one month after her speech, and it was just one more coincidence.

Center Shot Selfies partnered with the Jacksonville Icemen. Celia’s wife was handing out extra tickets at a Clay Chamber meeting when Tanya’s friend accepted the tickets and brought Tanya along. They stopped by the photo booth to take photos and say, “Thank you.”

The “eureka” moment outside the Jacksonville Icemen game was solace and compassion.

Celia held respect for the guards and was thankful that they did the best they could in an impossible situation for her family. Tanya resonated with the refugees and was impressed with their resilience against impossible odds.

Both women served in the U.S. Navy. Both women became entrepreneurs. Both have their businesses listed in the Clay County Chamber of Commerce. Both overcame trauma and hardship. Both choose empathy instead of despair. Both Celia and Tanya were in Guantanamo Bay 30 years ago.

Epilogue

While the 1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis would be the last major waterborne migration crisis, its aftermath led to adopting the “wet foot, dry foot” policy – Cubans who managed to make it to shore (dry foot) were granted U.S. citizenship. However, Cubans who were intercepted at sea (wet foot) were turned away.

Cubans continued to voyage across the Florida Straits for various reasons, usually in risky makeshift rafts without engines. The continuing U.S. embargo, which had lasted for decades, coupled with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, led to unbearable economic hardship. The Soviet Union sent the equivalent of about $4 billion in aid to Cuba, aid that Cubans could no longer count on in the 1990s.

The “Maleconazo” protest, which Celia describes in her memoir as occurring ahead of the 1994 crisis, was the largest anti-government demonstration Cuba had seen since the Cuban Revolution.

The wet foot, dry foot policy was in effect from 1995 to 2017. The U.S. continues to permit 20,000 immigration visas annually for Cubans.

There is a circulating American sentiment viewing Cuba as a sort of “Caribbean time capsule.” Because of the embargo, Cuba is known for the antique American cars that still drive through its streets, usually by its state-operated taxi industry. Despite the decades-long embargo, U.S. history is explicitly tied to the island.

Domestically, Cubans make up a sizable ethnic group in Florida. Most Cuban Americans live in Florida; according to the U.S. Census, 6.5% of Floridians can trace Cuban ancestry.

Ending the wet foot, dry foot policy in 2017 did not end Cuba’s migration crisis. Instead, it manifested differently.

Shortly after reopening its borders following the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuba agreed with Nicaragua to freely allow travel between the countries without visa requirements.

Sen. Marco Rubio, the son of Cuban parents, considered the agreement to be a hostile act.

“The Ortega-Murillo regime (Nicaragua) is aiding the Cuban dictatorship by eliminating visa requirements to instigate mass migration to our southern border,” Rubio said in 2021.

Since 2021, it is estimated more than 500,000 Cuban refugees have flown from Cuba to Nicaragua and have traveled north to the U.S.-Mexico border. Guerra estimates the number of refugees to continue growing to one million by 2026, making the 2020s the latest and most present migration crisis since 1959.