Celebrate Clay History

Grieving families demand an end to 1900’s convict leasing

Albert Weeks was just 17 years old when he shot and killed the man who mortally wounded his mother, Lora Weeks. It was August 11, 1911. The location was a place called Waller, in southern Clay …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Celebrate Clay History

Grieving families demand an end to 1900’s convict leasing

Albert Weeks was just 17 years old when he shot and killed the man who mortally wounded his mother, Lora Weeks. It was August 11, 1911. The location was a place called Waller, in southern Clay County.

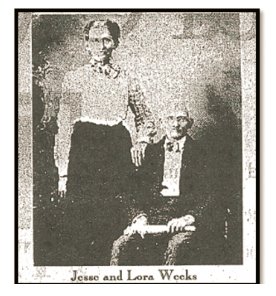

Jesse Weeks, Albert’s father, was away from home visiting his sick brother, Sheriff James Weeks. Jesse and Lora’s home were vulnerable, secluded out in the woods, with no men in the house. An escaped convict with the improbable name of William F. Williams slunk through the underbrush towards the Weeks’ home. Williams was 21 when he ran off from the T.W. Shands Turpentine Camp where he was “convict leased”. He planned to rob the Weeks Family in his desperate flight away from two life sentences and towards freedom.

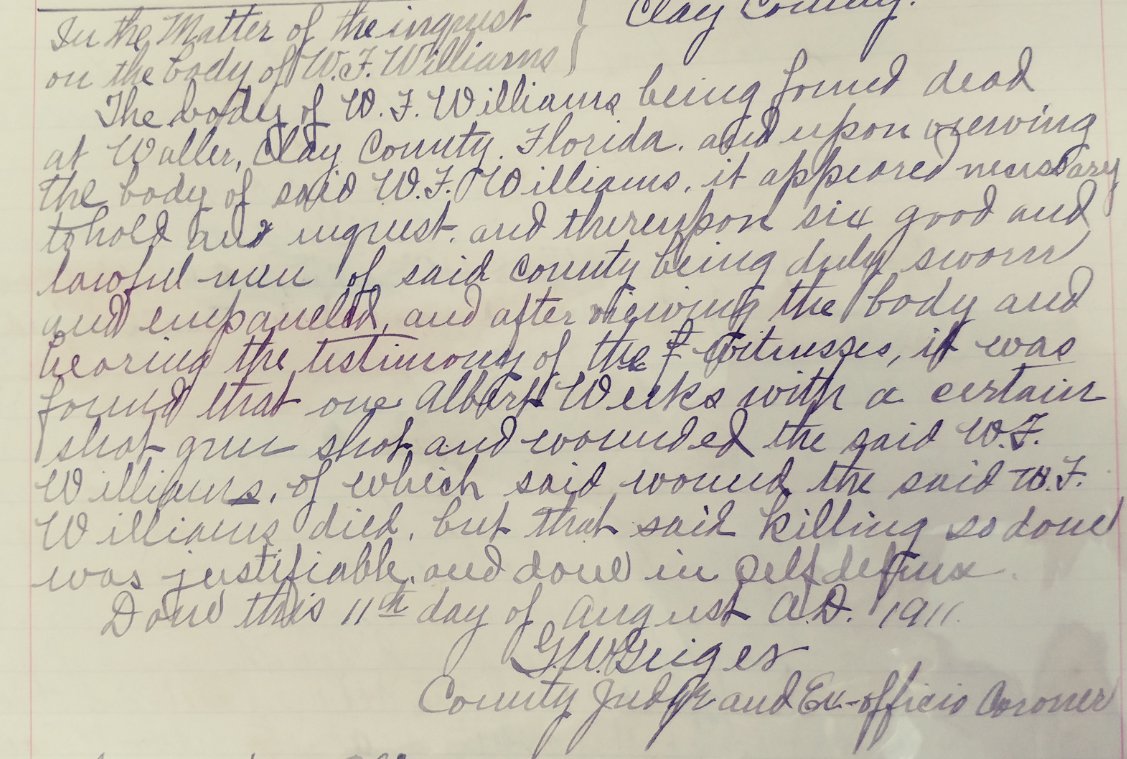

It was pitch dark that night. The sound of tree frogs and crickets most likely drowned out the approaching, crunching sound of Williams’ footsteps on the gravel near the home. Williams made his move and broke through the front door. Lora Weeks and her children were terrified. Williams shot Lora. Albert shot and killed Williams, but not before Williams wounded Albert in the ankle and not in time to save his mother who died instantly there in the home. The coroner’s

dryly-written inquest report lacked any detailed description of the horror of that night, describing Lora’s death as “one of other than natural causes” and a homicide.

Young Albert Weeks was lauded a hero by the citizens of 1911 Clay County. His shooting of the escaped convict was deemed justifiable homicide at the coroner’s inquest, held the same day as the one involving his mother’s death. Two hapless fellows, Bert Creekmore and Robert L. Creekmore, were named as accessories before the fact in the inquest even though records reveal no real evidence linking them to the crime. This was proven true when, on August 23, 1911, Circuit Judge Rhydon M. Call, granted the cousins’ writ of habeas corpus petition after the judge found no probable cause. The two high-tailed it back to their hometown of Live Oak and lived decent lives until they died young, in their 40’s.

The Weeks Family lost a wife and mother that terrible evening, so their grief was deep. Their beloved Lora was Lora Lane before she married Jesse Weeks in 1874. Lane Avenue in Jacksonville is named after her prominent family. Lora and Jesse had five children together: Albert, Amos, Mamie, Nanney and Alice. Jesse faced raising his children alone. Things got worse for Jesse Weeks when, just a few weeks later, on August 24, 1911, his brother, Sheriff James Weeks, died, too. It was a dark time for the entire Weeks Family.

None of this would have happened if not for a practice known as “convict leasing”. Turn the clock way back to July 17, 1905. William F. Williams was working as a clerk in a clothier in Pensacola. He decided that his employer John White had slighted him when he accused Williams of stealing. Williams left work and came back drunk and armed with a gun. He calmly gunned down Mr. White, fellow employee Edwin Dansby and two other clerks, killing both White and Dansby. He went on trial twice, was convicted twice, and got a life sentence in each case. The juries recommended mercy instead of death, which set off a tidal wave of protests by the citizens. The juries were called “cowardly” and much worse.

Williams was sent off to prison where he became one of the hundreds of state prisoners leased to private turpentine camps. In return, the state was paid for the prisoners’ labor. This convict leasing system was akin to peonage, slavery by another name. Security at the camps was far laxer than at a prison, which is where Williams should have been. Work conditions were brutal and fatalities occurred.

In those days, Clay County was running its own convict work camp in addition to regularly leasing out its own jail inmates. The local camp was located near Doctors Inlet, where the college now stands. These convicts were required to work on county projects but sometimes were also farmed out to private concerns. In order for the program to not be peonage in the eyes of the law or outright slavery, prisoners received a discharge fee when they finished their sentence.

However, the convict lease system was short-lived here, brought to an end by the infamous actions of Clay County citizen Thomas Walter Higginbotham. Higginbotham worked as a state guard for the T.W. Shands Company in Belmore (now Belmore State Forrest) since about 1918. In 1923, Martin Tabert, a young man from North Dakota, was arrested on a charge of vagrancy in Tallahassee, Florida. Tabert was convicted and fined $25. Although his parents sent $25 for the fine, plus $25 for Tabert to return home to North Dakota, he was never given credit for the payments by the Leon County jail system. Talbert was then leased to the Putnam Lumber Company in Clara, Florida, in Dixie County. Once there, the whipping boss, the same Thomas Walter Higginbotham, flogged Tabert to death. Nationwide press coverage of Tabert’s killing and his grieving family earned one newspaper, the New York World, the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

Higginbotham received a 20-year sentence, which his lawyer, Leonidas Wade of Orange Park, immediately appealed. While out on a $10,000 appellate bond, Higginbotham resided in Green Cove Springs with his wife and 4-year-old son. Records list Higginbotham as single by 1930 and show he died in Jacksonville in 1939. Twelve years after Lora Weeks was needlessly killed in her home by escaped leased convict and convicted murderer William F. Williams, Florida’s 23rd governor, Cary Hardee, ended the system of convict leasing in 1923. This was done, at least in part, due to the Talbert case that year and the negative publicity that followed. In the hearts of Clay County’s Weeks Family, the decision was made more than a decade too late.